Public Works

November 11 - December 16, 2023

Art in the Park is pleased to present David Weldzius’s “Public Works,” an exhibition that brings together three projects that meditate on free speech, the right to the city, and welfare initiatives that have aided ordinary people in times of grave economic hardship.

Upon entering the gallery, one first encounters a series of plywood boxes, sculptures screen-printed with the graphic logos of soap and detergent brands. Flipped upside down, Weldzius’s soapboxes recall the makeshift crates that agitators once preached from—in public parks and on street corners—since the early nineteenth century. While soapboxes have traditionally been used to galvanize political and spiritual communities, they are equally marked by the interests of commerce—an apt analogy to the exercise of free speech on social media platforms. Undeterred by the predictable antagonisms of direct democracy, Weldzius offers his platforms for spontaneous acts of expression, inviting speakers and listeners alike to consider the value of the spaces that we occupy and maintain in common.

The municipal building where Art in the Park is headquartered was originally a clubhouse for lawn bowlers. The surrounding park and the nearby freeway were constructed by local workers under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration, which provided employment during the Great Depression. Weldzius has displayed works from his series Relief on the fireplace mantel. Relief consists of plaster copies of the dates 1937 through 1940, impressed on the concrete parapets of nearby freeway overpasses. Weldzius has enmeshed “1939,” a plasterwork that marks the building’s year of construction, with the façade of Art in the Park.

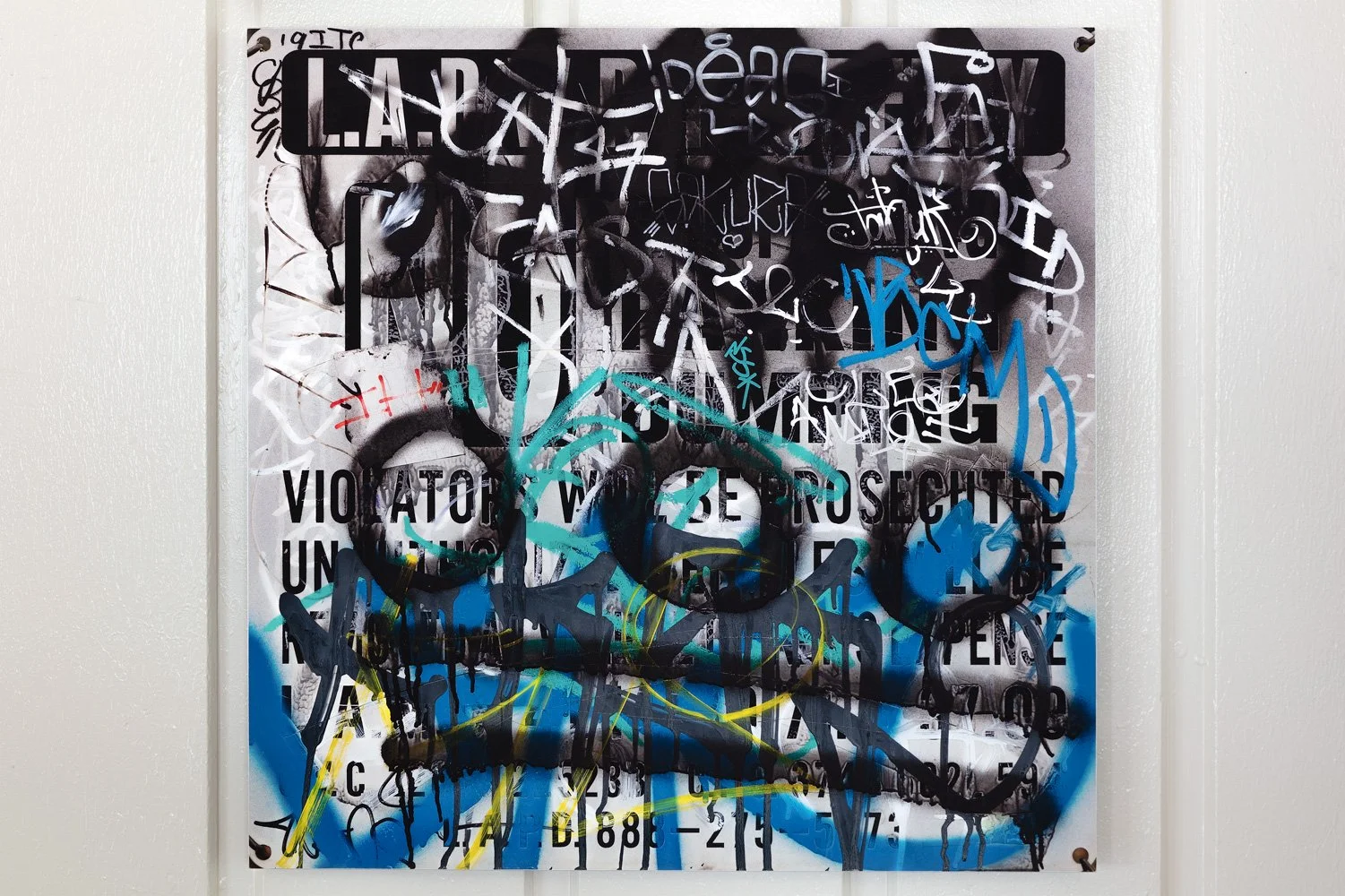

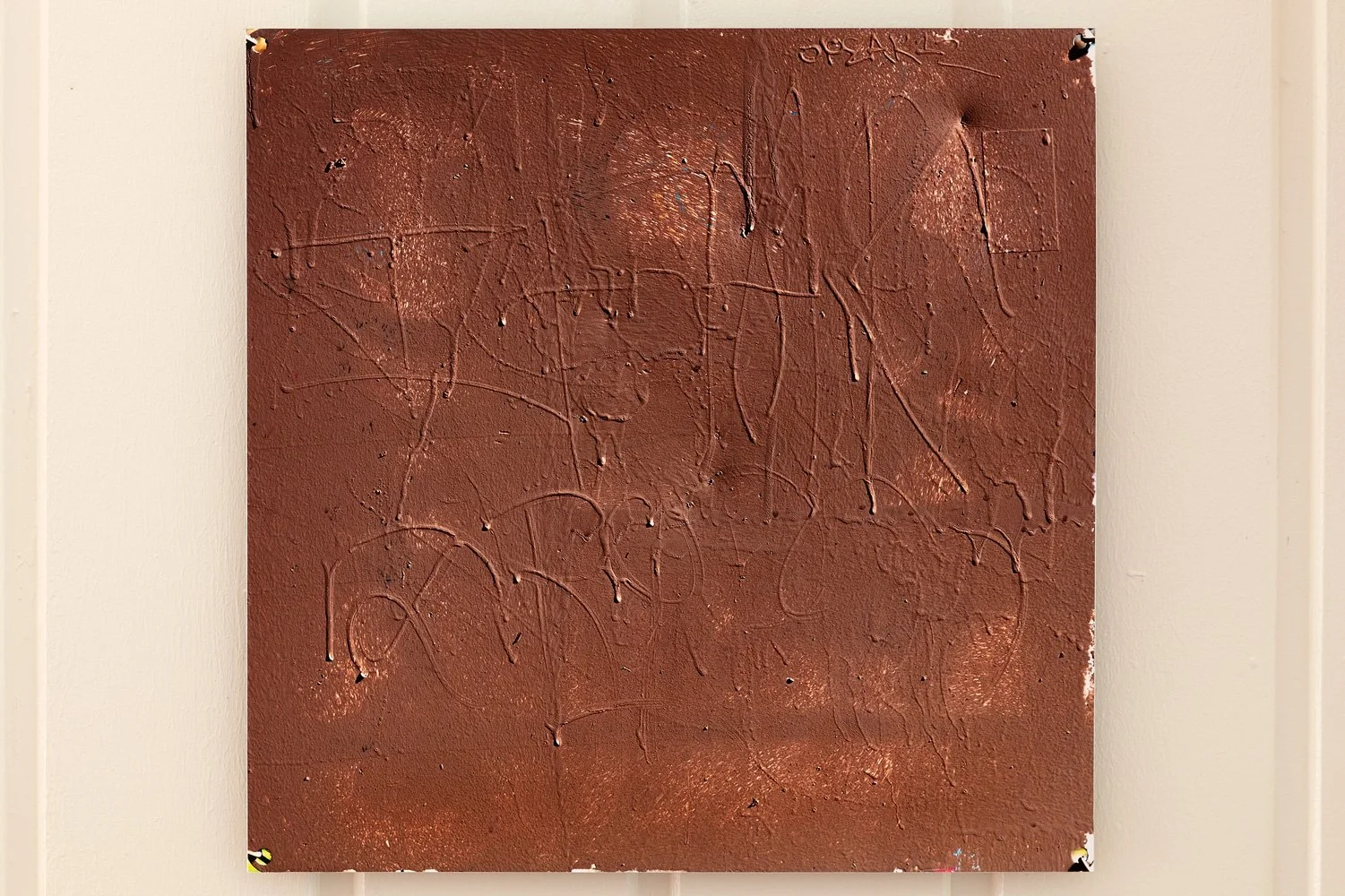

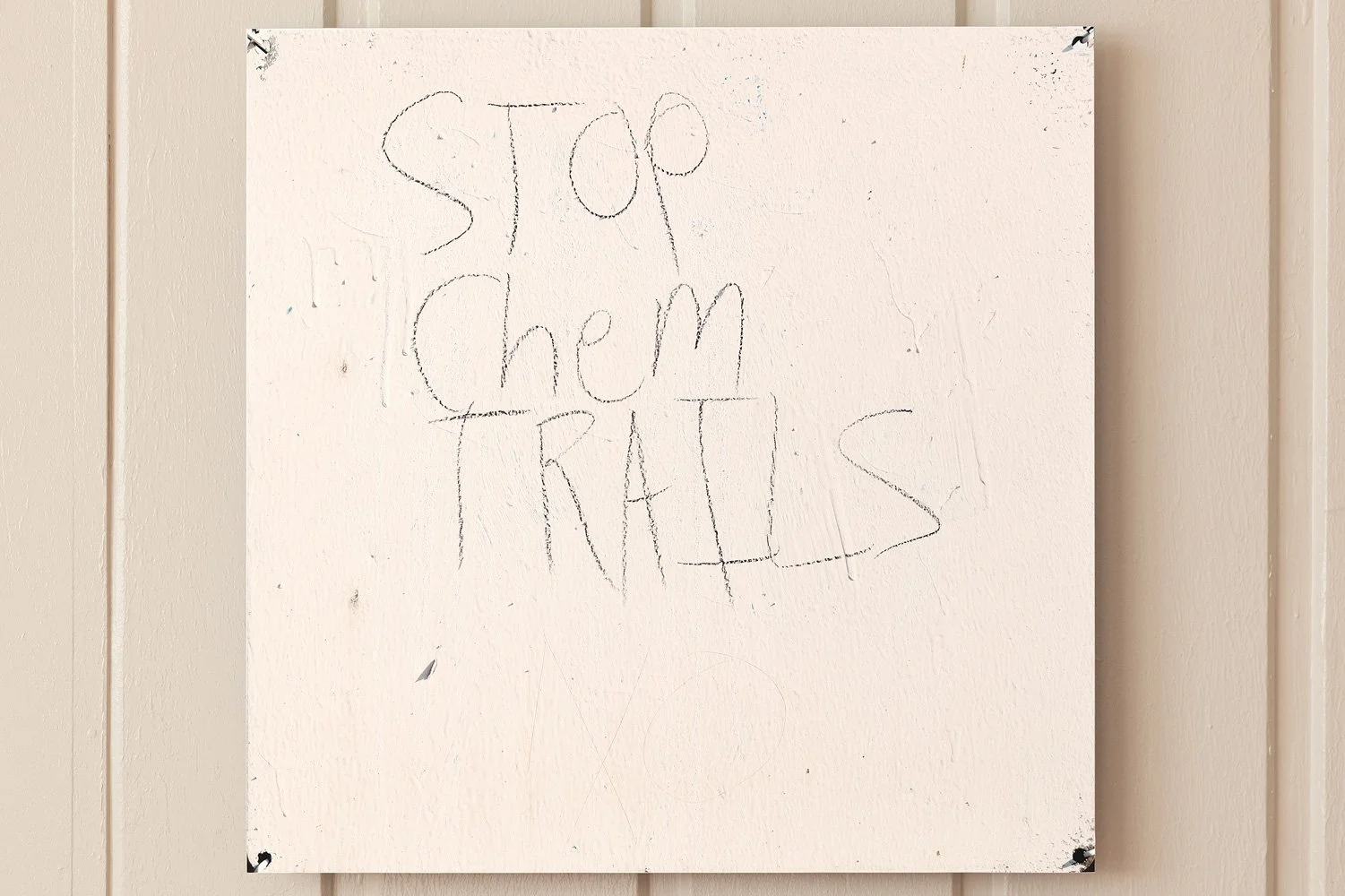

Last, Weldzius will debut History Painting, a series of photographs of “No Trespass” signs which surround a nearby reservoir. The signs are covered in colorful layers of graffiti applied by anonymous contributors. These markings are routinely painted over and redacted by city workers before being tagged again. Photographed weekly, Weldzius’s series traces a history of citizens marking their presence on restricted public land. For Weldzius, the palimpsests (literally the writing on the wall) evidence a spontaneous act of resistance to privation—low wages, high rents, police violence, and climate apathy, among other grievances.

“Public Works” captures the collaborative and antagonistic spirits with which we occupy spaces that are increasingly vulnerable to private usurpations. Weldzius at once celebrates and criticizes the historical use of theses spaces, nevertheless offering a hope-claim for their future.

David Weldzius: Public Works

Art in the Park: 5568 Via Marisol Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90042

November 11 - December 16, 2023

Opening Reception: Saturday, November 11,

2 - 6 PM

“Arroyo Seco storm drain showing excavation in the main channel below the old Avenue 52 bridge, February 15, 1937.”

11 x 14 in. matted silver gelatin print, photographer unknown (photo courtesy of USC Library)

No title (53_10 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (47_00 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (29_09 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (45_09 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (15_09 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (4_00 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (5_00 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (12_16 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

No title (07_06 from the series History Painting), 2023

24 x 24 in. pigment print mounted on aluminum

“1937” (from the series Relief), 2013/2023

18 x 8 ¾ x 1 ¼ in. plaster work

“1938” (from the series Relief), 2013/2023

18 x 8 ¾ x 1 ¼ in. plaster work

“1940” (from the series Relief), 2013/2023

18 x 8 ¾ x 1 ¼ in. plaster work

“1939” (from the series Relief), 2013/2023

18 x 8 ¾ x 1 ¼ in. plaster work

Soapboxes, 2023

Screen-printed plywood, dimensions variable

Since March of 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, I have been hiking around Ascot Hills, a public park near my home in Northeast Los Angeles. The park features a reservoir surrounded by a tall chain-link fence studded with razor wire. The city has posted sixty-six signs around the reservoir. Each is 24-by-24 inches and affixed to the fence at eye-level. The signs read:

LADWP PROPERTYNO TRESPASSING

NO PARKING

NO DUMPING

VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED

UNAUTHORIZED VEHICLES WILL BE

REMOVED AT VEHICLE OWNER’S EXPENSE

LAMC 41.14-80.71.4-37.09

LAPD 888-275-5273

I became interested in the Department of Water and Power signs when I noticed that they had been tagged recurrently with sharpies, crayons, stickers, and spray paint. Equipped with a paint roller, a vigilante graffiti-buster periodically redacted these markings. Covering the surface in opaque layers of white, grey, black, and brown housepaint rendered the message illegible, stripping each sign of its intended function--to deter the public from trespassing--while providing a tabula rasa for fresh markings. The cat-and-mouse game between taggers and graffiti busters dwindled in the fall of 2021, soon after local schools reopened their doors.

The signs at Ascot Hills evidence a thick tangle of errant and deliberate markings, many of which are not legible to the typical passerby, including myself. Nonetheless, I was intrigued by the collaborative and antagonistic spirits of cumulative mark-making and obfuscation that each sign bears, so much so that I decided to photograph them over the course of several months.Who contributes to the palimpsests on display? Members of neighborhood gangs, certainly. But also, environmental activists, Dodgers fans, people who love Jesus, people who share music on Sound Cloud, conspiracy theorists--and people who loath Donald Trump, the LAPD, and former mayor, Eric Garcetti--among others.

Tongva people hunted and gathered in what is now called Ascot Hills until 1781, when the land was seized by the missionaries of San Gabriel. Settlers used the land for grazing livestock because it was too hilly for cultivation. Today, the wild mustard that blankets the hills of El Sereno in the wet season beckons the chattering ghost of Spanish colonial rule. In 1831, the land was sold to Mexican rancheros and renamed Rancho Rosa de Castilla after the native roses that flourish on the banks of the stream. After California entered US statehood, the land parcels were seized once again and sold off to developers. The City of Los Angeles purchased the land in 1910, and it has been used for municipal water capture and storage ever since. The park is named after the Legion Ascot Speedway, a racetrack that surrounded the reservoir from 1924 to 1936.

The Greek word “nomos,” meaning “law” or “custom,” is likely derived from “némos,” which means “a wooden pasture” or “glade.” In Capital: Volume One, Karl Marx recalls a time before primitive accumulation in which many of the pastural lands of preindustrial Europe were commonly owned and ruled. Leaning on Adam from Hebrew scripture to offer a critique of Adam Smith’s concept of previous accumulation, Marx writes:

Primitive accumulation plays in political economy the same part as original sin in theology. Adam bit the apple, and thereupon sin fell on the human race. Its origin is supposed to be explained when it is told as an anecdote of the past. In times long gone-by, there were two sorts of people; one, the diligent, intelligent, and, above all, frugal elite; the other, lazy rascals, spending their substance, and more, in riotous living. Thus, it came to pass that the former sort accumulated wealth, and the latter sort had at last nothing to sell except their own skins. And from this original sin dates the poverty of the great majority that, despite all its labor, has up to now nothing to sell but itself, and the wealth of the few that increases constantly although they have long ceased to work. Such childishness is every day preached to us in the defense of property.

Of course, the forceful expulsion of people from Ascot Hills along lines of ethnicity, tribal affiliation, or national identity (or lack thereof) is merely one case study in a much larger colonial project. However tonight, rather than taking you down that well-worn path, I hope to take you down another. Let’s talk instead about the Eden on the other side of the rose thorns and razor wire, and the barrier that separates Angelenos from the water that we draw from our taps.

Offering a dialectical antithesis to Irving Berlin’s trite anthem, “God Bless America,” Woody Guthrie croons:

As I went walking I saw a sign thereAnd on the sign it said "No Trespassing."

But on the other side it didn't say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

At risk of misreading the writing on the wall, I want to argue that the markings on the LADWP signs offer a spontaneous resistance to privation--low wages, high rents, police violence, and climate apathy amongst the ruling elite, among other grievances. Their markings, whoever they are and whatever they say, demand an autonomous right to the city, the wholesale reapportionment of Eden to the commonwealth.

Indeed, I can think of public projects that make explicit claims to autonomy, some not far from the Eden in question. The murals of Estrada Courts and Ramona Gardens, both public housing developments in East Los Angeles, give voice to low-income occupants therein. Judy Baca’s “Great Wall of Los Angeles,” painted on the concrete walls of the Tujunga Wash in North Hollywood, explicates a people’s history of the city. While these projects represent coordinated efforts to draw attention to marginalized communities, their histories, and struggles, the mark-makers of Ascot Hills are independent actors whose contributions, instead, instantiate the exercise of free will in common space.

Jurgen Habermas writes:

A portion of the public sphere comes into being in every conversation in which private individuals assemble to form a public body[…]Citizens behave as a public body when they confer in an unrestricted fashion.

By my estimation, the spontaneous mark-making at Ascot Hills proposes a more active relationship between people and publics, inciting a constellation of discordant expressions without monetizing or surveilling the speech of those who opt to participate or to bear witness. Eluding the First Amendment’s steady co-option to the autocratic, profit-focused terms of communication capitalism, these markings offer a hope claim for the future use of the commons.

Insofar as nomadic people utilized and maintained the reservoir long before it was adapted to serve the demands of municipal water management, the historical achievements of Los Angeles water can no longer fall squarely on the shoulders of Frederick Eaton, William Mulholland, or the Army Corps of Engineers. On the other hand, when municipalities betray their civic duty to provide clean water for the masses--as has been witnessed in Flint, Michigan and more recently in Jackson, Mississippi--I cannot help but wonder how lives would be impacted if common resources were once more occupied and regulated in common.

At risk of plunging into the depths of naïve prefiguration or grasping for solutions that fall within the jurisdiction of domestic terrorism, let’s imagine a scenario in which the fences and signs that restrict access to the reservoir were razed and removed by popular will. For an inversion of power at this magnitude to become reality--for the people of Los Angeles to conspire to “storm heaven,” to borrow Karl Marx’s characterization of the Paris Commune--surely a novel uprise on par with Ferguson, Zuccotti Park, or Tahrir Square would be in order.

Coincidentally, since the collapses of SVB and Signature Banks last week and the generous bailouts that will undoubtedly ensue, the horizon of popular revolt is suddenly much closer than previously believed. However, this time let’s imagine a popular movement that, rather than reacting to crises as they surface, acknowledges a permanent state of crisis--like a nation-state that, after years of common tragedy, has betrayed the prospect of raising the flag beyond half-mast.

In this state of affairs, the occupants of the commons could record their wishes and demands on a people’s chalkboard. And if we can agree that the disaffected sign- writers of Ascot Hills are, in fact, latent radicals, then surely this project has already begun.

Thank you.

David Weldzius

March 16, 2023

Valencia, California